Nvidia: If Only Denny's Was As Big As This Company

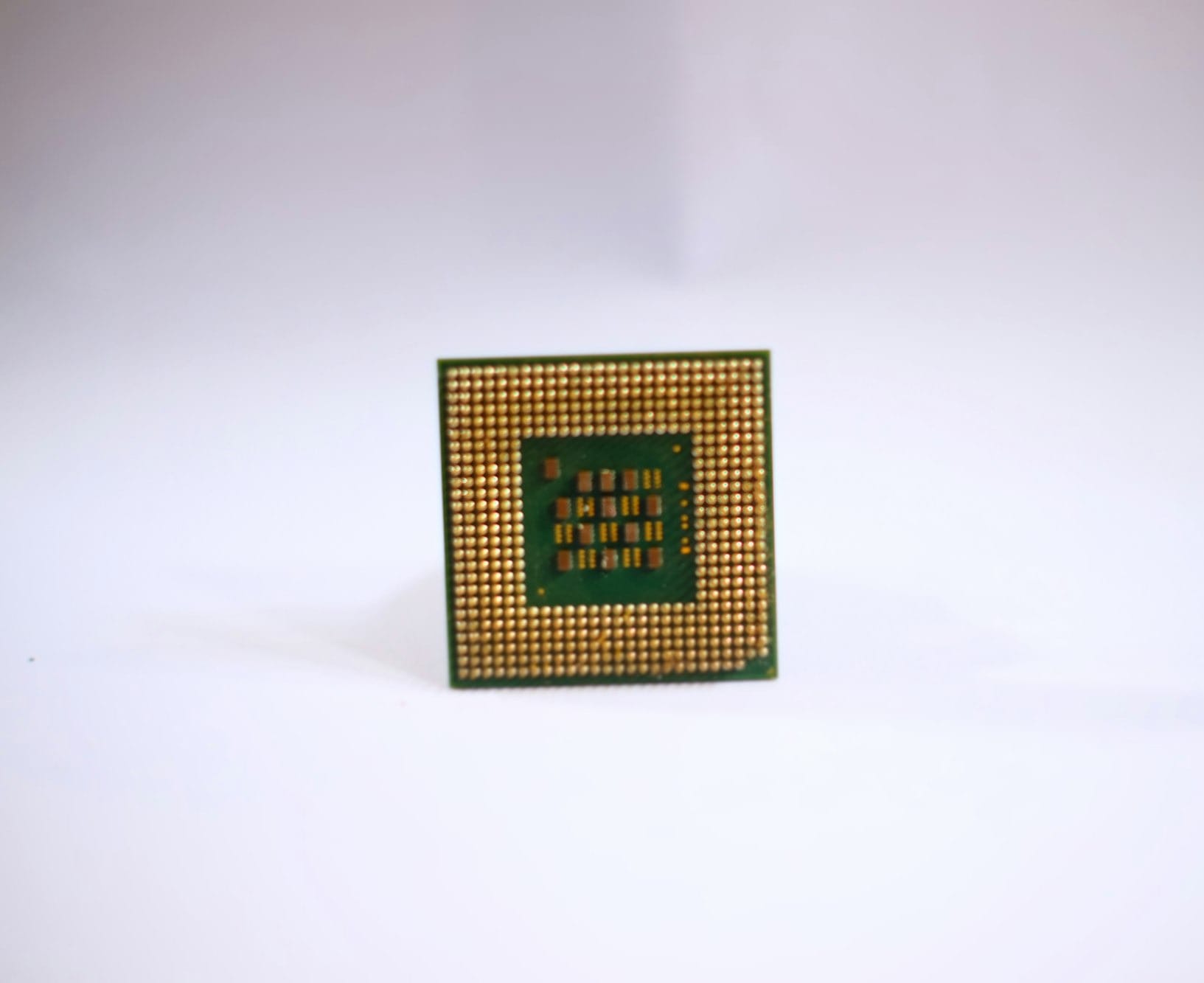

If you were trying to design what is currently the world's most valuable company from scratch, you probably would not start in a Denny’s. You would not pick a market with ninety competitors. And you probably would not try to make hardware, which is expensive, slow, and unforgiving at the time. Yet that is exactly how NVIDIA began. Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem sat in a booth in San Jose in early 1993 and imagined a future in which computers would not think like they did in the past. The industry was still centered around the CPU, a general purpose workhorse. They believed a different style of computing would eventually matter more, one that used thousands of small calculations in parallel. That idea was abstract at the time, but they saw a path to make it real through graphics. Games were becoming more complex, and visual computing needed a new kind of chip. If they could build it, they knew there would be demand.

It was not an obvious choice, though. Graphics chips were a commodity business with thin margins and lots of competitors. But Huang had already spent years in semiconductors, and he understood two things very clearly. First, that graphics computation mapped naturally to parallel processing. Second, that the personal computer was about to experience a wave of visual intensity that the CPU could not handle alone. Malachowsky and Priem shared that conviction, and the three pooled about forty thousand dollars to start NVIDIA in April 1993.

Their first product, the NV1, was bold. It tried to combine two dimensional graphics, three dimensional acceleration, audio, and even support for Sega controllers into a single card. However, the industry began to coalesce around the Direct3D standard that Microsoft supported, and the NV1 simply was not aligned with what game developers wanted. It was too ambitious and built around the wrong approach to rendering. The result was a commercial failure. For a young hardware company that had not yet found its footing, this could have been fatal.

Instead, NVIDIA executed a pivot with remarkable speed. They dropped the NV1 approach and reorganized their roadmap around emerging standards. The team released the RIVA line, starting with the RIVA 128 in 1997. It was fast, compatible, and more importantly, it showed that NVIDIA could build competitive chips on an aggressive schedule. This agility, the ability to abandon sunk costs and realign around the market, became a signature of the company. Many startups talk about moving fast. NVIDIA proved it in a sector where moving fast is usually impossible.

By 1999 the company had enough momentum to go public. That same year it released the GeForce 256, the chip that NVIDIA marketed as the first GPU. It could execute transformation and lighting operations on the chip itself, lifting heavy work away from the CPU and unlocking more complex games. The timing was perfect. Gaming was entering a golden age, and PCs needed the power. GeForce turned NVIDIA into the leader of discrete graphics. Soon after, Microsoft chose NVIDIA to provide hardware for the original Xbox, bringing a large contract and global visibility. This momentum did not come easily. The Xbox project strained the engineering team and diverted resources, but NVIDIA used the pressure to strengthen its internal processes instead of breaking under them.

Nvidia IPO

Hardware requires enormous capital, long development cycles, and the ability to fund several product generations before any of them pay off. By the time NVIDIA had released its RIVA line and was preparing the first GeForce chip, the company needed a far larger financial base than venture funding or operating revenue could support. The IPO gave NVIDIA the capital to scale manufacturing, invest heavily in research, and compete in a market where speed and iteration decides winners. It also gave the company credibility with partners like Microsoft. The IPO was one of the company’s most important decisions, because without that influx of capital and legitimacy, NVIDIA would not have had the runway to build the GPUs and software platforms that would be foundational.

Through the early two thousands, the company sharpened its product cadence. New architectures arrived regularly, each iteration delivering more performance, more programmability, and more developer control. NVIDIA learned that hardware alone was not enough. To win the long game, the company needed software that would let developers use the chip for more than just graphics. That thinking led to one of the most important strategic decisions of Jensen Huang’s career.

Beginning around 2004, NVIDIA invested heavily in a project that had no immediate commercial payoff. The idea was to create a programming model that allowed developers to write general purpose code that ran on the GPU. The project became CUDA. It launched in 2006 for early adopters and in 2007 for the broader market. CUDA gave developers a way to use the parallel nature of the GPU for scientific computing, simulation, finance, medical imaging, and eventually artificial intelligence. It created an ecosystem around NVIDIA’s hardware. Switching away later would become extremely difficult because tools, code bases, and research workflows were built for CUDA. It was a long term bet that absorbed massive resources, but it positioned NVIDIA for the most important shift in modern computing.

When deep learning began to show practical results around 2012, researchers looked for hardware that could train neural networks quickly and efficiently. The best option was the GPU, and the best GPU environment was NVIDIA’s. CUDA became a bridge between the old world of graphics and the new world of artificial intelligence. This pivot from gaming to general purpose compute transformed NVIDIA from a strong niche player into the central supplier for the most important computing wave of the century.

The numbers reflect the impact of that shift. In 2013 the company generated about 4.3 billion dollars in revenue. By 2024 annual revenue had surpassed sixty billion, driven overwhelmingly by data center products built for AI. Chips like the V100, A100, and the H100 became the standard for training large scale models. As AI research accelerated, NVIDIA captured more than eighty percent of the market for AI training hardware. The company that began as one of many graphics card makers evolved into the primary infrastructure provider for artificial intelligence.

What makes NVIDIA unique is not only the products it created but the way it built them. Huang runs the company with a level of technical involvement that is rare for a chief executive of a multibillion dollar corporation. NVIDIA operates on long horizon roadmaps that stretch across several product generations. It integrates hardware design, software tools, and developer ecosystems into a single stack. Instead of treating chips as commodities, it treats them as platforms that enable entire industries. This philosophy, the belief that control over the full stack creates defensibility and value, is one of the main reasons NVIDIA has outpaced competitors.

The company also learned to avoid complacency. The early failure of the NV1 taught the founders that markets move quickly, standards shift, and customers are unforgiving. NVIDIA built a culture where engineers are encouraged to rethink assumptions, challenge internal decisions, and rebuild architectures when needed. That culture allowed the company to enter new fields, from automotive computing to robotics to cloud services, without losing momentum in its core markets.

There is also a lesson in how NVIDIA handled its competitive environment. Instead of trying to beat CPUs head on, NVIDIA built around them. Instead of fighting for commodity pricing, it created specialized value. Instead of letting software layers sit above the hardware and weaken the customer relationship, it built software that pulled customers closer. This is vertical thinking. It is the idea that owning the layers around your product creates leverage, trust, and long term defensibility.

Today, NVIDIA is one of the most influential technology companies in the world. It shapes artificial intelligence, scientific computing, autonomous vehicles, and gaming. It produces chips that sit at the center of every major AI breakthrough. And yet the core lesson remains the same as it was at that Denny’s table in 1993. Pick a fundamental shift early. Build for the future, not for what the market already understands. Do not chase every direction. Commit to one view of the world and let time compound it.

Works Cited

- Lohr, Steve. “A Bet on Graphic Chips Pays Off for Nvidia.” The New York Times, 26 Nov 2006.

- Markoff, John. “The Transformation of the GPU into a General-Purpose Processor.” The New York Times, 29 Nov 2006.

- “Nvidia Corporation Form S-1 Registration Statement.” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, filed 1999.

- Chan, Rosalie. “How Jensen Huang Built Nvidia into a Trillion-Dollar Powerhouse.” Business Insider, multiple reports 2023–2024.

- Metz, Cade. “Nvidia’s Moment Has Arrived.” The New York Times, 2023.

- “Nvidia Corporation Annual Report 2024.” Nvidia Investor Relations.

- “Nvidia Introduces the GeForce 256, the World’s First GPU.” Nvidia Press Release, 1999.

- “Nvidia and Microsoft Announce Xbox Graphics Partnership.” Microsoft News Center, March 2000.

- Clark, Don. “How Nvidia Won the Race for AI Chips.” The Wall Street Journal, 2023.

- Shankland, Stephen. “CUDA Turns 10: How Nvidia’s Bet on AI Paid Off.” CNET, 2017.

- “Top500 Supercomputer List.” Top500.org, 2024 Data.

- “Nvidia Revenue and Market Share Statistics.” Statista, updated 2024.

- “Nvidia’s Jensen Huang on the Birth of CUDA and the Future of AI.” MIT Technology Review, 2021.

- “Nvidia.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed 2025.